Luisa read in smooth and raised lettering: Smith & Sons Glass Works Hadleyburg, OR. User beware. Contains your distilled star-heart. No Warranty. Will not replace if lost or damaged. Smith & Sons Glass Works Hadleyburg, OR. She could not think of why anyone would put a thing like that onto a mason jar. She could not remember where she had bought it, but here it was at the back of her late mama’s kitchen cupboard– behind the ‘trastes’ that had been saved for too long. When the phone rang, it was a grassroots campaign for the upcoming election. She replied in a non-committal answer, thickening her accent so they’d let her off the line. Then, with the jar still in hand, Luisa blinked at the vessel and remembered what she had been doing. She went ahead and filled it up with long grains of beautiful ivory rice.-FM

Author: Fox Mederos

Inktober Eleventh. “Cruel.”

Miles will never forget when Russel pulled him into the huddle of spitting and cursing older boys behind the mall parking lot after school, his freshmen year. Miles listened with a growing excitement at the rules. He ignored the complaints about him. And tried not to get too nervous or agitate his own lungs.

Hey listen up, called a loud boy with acne. We’re each going to choose our teams. If you’re not in a car you’re running away from one. If you’re running from a car, you have to run and hide until one of the riders tags you. Car tag lasts until morning, he said and the older boys all mumbled agreement. Suddenly Miles could feel his pulse surging in his ears, already thinking of him and his brother riding together. With the radio on. And windows open. He couldn’t help but smile.

Let’s choose teams, said the loud boy with bad acne.

The older boys thundered all together: not it.

They were howling, laughing, falling out and running for Russel’s car. In his mind’s eye, Miles can see Russel’s baseball jersey pulling and billowing over his shoulder blades while he runs with them. Away from Miles. Who suddenly felt.

Short of.

Breath.

Inktober Ninth. “Precious.”

Inktober Eighth. “Star.”

The thing hung swinging in that night sky with such a grace that it reminded Arthur of the tail in his mother’s grandfather clock, which he used to play with as a boy so that occasionally they’d have to open its face and wind the cogs right-ways again. But tonight the thing was amid the tangle of stars out in the dark above the pines that he could see in the view from his bed, a strange sort of light shining. I’ll be damned, he thought. All of him was rubber and sore from the mill fire but what with that thing swinging there, fired his curiosity. Arthur stayed watching it, thinking of the big ticks and tocks of that old clock until he couldn’t stay still anymore. The sound of it in his mind pushed him up and out of bed.

Riles was a big man with Sioux blood in him and thick dark hair. He was the oldest but a smooth face like a baby’s. In the room of snoring men, he got up when Arthur did and started getting on his shirt and scrambling for his things in his bedside so that Arthur had to hush him. “It’s okay,” Arthur said. “It’s only some foolishness of my own.” Riles sat nodding. His eyes were still closed but he came with Arthur just the same, out into the dark outside the station.

The frigid air filled Arthur up. The station house was barely lit by spotlights in the shoulder of the mountain road. An island of light in the tall shadows of trees, only a flagpole and Arthur standing here. Riles came out from behind the screen door in shorts and his boots while Arthur breathed into his hands. They began to search the sky and then, there it was. “Look at that how it’s sliding up and down.” Arthur indicated with the full extension of his arm.

“Helicopter, probably.” Riles said.

“Nah.” Arthur said. “They don’t sway like that. You ever seen any helicopter or airplane sway all side-wise like that.”

Riles was quiet long enough for Arthur to feel foolish. When Riles lit himself a cigarette he seemed to take another look at the thing. “It’s changing colors now.” said Riles.

“Hell, I can see that.” Arthur said.

“Well, maybe we should get the chief on the line. Could be terrorists.”

But Arthur thought on that. It had been a long day, what with the mill that came down and Pete stuck at the ground floor. And the way Pete’s father crumpled up at the news and cried while he held onto Arthur – so they were both shaking. And neither man felt as if they could look at each other after that. Riles interrupted his thoughts.

“Why do you never share what you are thinking?” Riles asked.

Arthur shrugged. “I don’t ever know what you’re thinking either,” he pointed out. “Come on then. Tell me, Mister Sensitive.”

A Datsun came up and back down the mountain pass until it was only red tail lights in the dark twist of the single-lane highway, never stopping to see the shape in the sky. Arthur wasn’t sure he was tired of looking at it yet, but he felt more and more foolish. There was no logical outcome for spectating shapes in the sky. There would be no grand reveal or jack-pot payout. He would go home and sleep for a day, eat badly for the next couple days after. Then he would come back to Whistle Wood House, full of men he did not know, and who didn’t know him.

Behind the glowing cherry of his cigarette, Riles began: “It makes me think of the first time I saw something like this, my first year away from home in Reno where I grew up. I was with my girl and falling asleep on the couch, too tired from drills at the Airbase on the other side of the mountain . . .”

She gets to touching me. Trying to keep me awake. Just then her father came into the living room and asked us if we wanted to look at the thing he had been looking at from his bedroom window. Her father always had a way of making me stand straighter or lean forward when he was in the room. He had known my family and I always felt like he was waiting for me to prove bad ideas he had about me right. Well, when we went outside together he showed me lights just like that one there. But it was three of them. And a low humming. I remember it looked like they were hovering for a while out there. And we three watched them all night. And I felt this place was welcoming me.

After a while Riles went in and put on coffee while Arthur stood until the sun rose. And the light was still a pin-point in the egg-shell blue morning.

Inktober the Seventh. “Exhausted.”

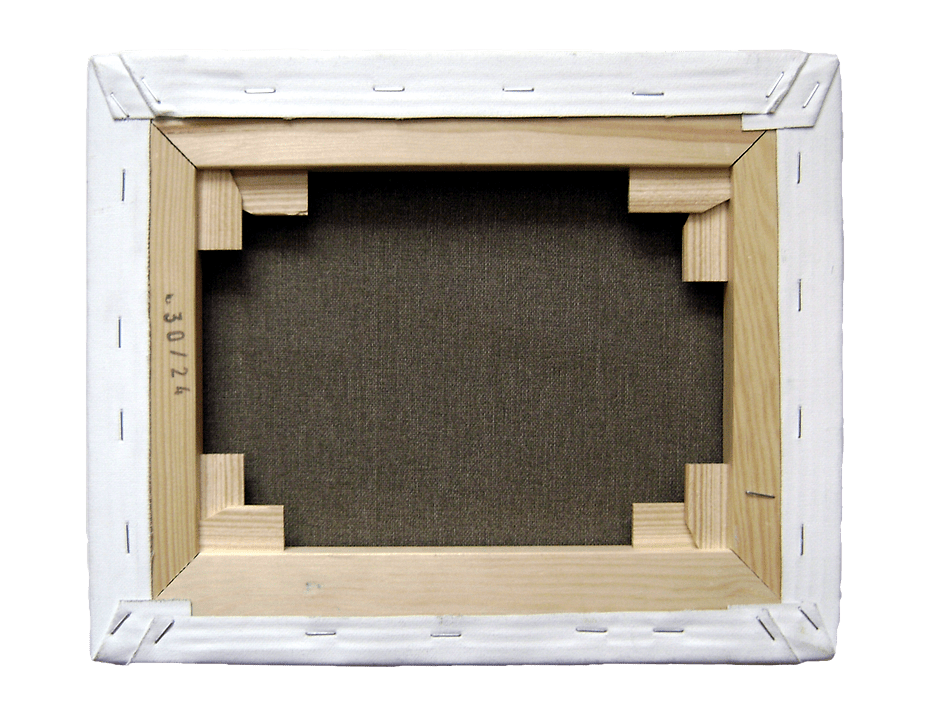

Charlie punches staples into thin wood pieces until they fit into a frame. His calloused hands are rough and fast and numb to the rough biting grain. Except for the sudden staple through his nail bed. And a single crimson bubble . . .

When he is finished getting the toilet in 2A to flush right, Charlie doesn’t go to sleep. He puts out the paint-splattered canvas all over his room so that the whole floor, the furniture, and the bed, looks like a Pollock. Alone in the room painting with Merle Haggard on the brassy sounding radio, he continues painting. When he finishes, he steps back — looking a long time.

There is drama upstairs again; Linda knocks on his door to come fast about some shouting up there. A strange call for a handyman, Charlie thinks but Linda is also trying to get a look into his room — at his series on the Whistle Wood Blackout. Charlie presses the door shut to get dressed quick and by the time he gets up to 2A the police are involved, chatting and laughing but mostly asking around about what is clearly some dirty between two guests. The fight is about the thermostat that doesn’t work. A rattling keeping them up. Charlie opens up the vents in the room. And finds a ring.

He keeps it. And tells them the rattling is fixed.

Charlie takes up another set of wood pieces. With a bandage on and the ring fit over his thumb, he begins to trace the outline of his underpainting again. Beneath his pencil — a dozen discarded shoes. It is almost morning again.

Inktober Fifth. “Chicken.”

Dear Lillian,

The sage you burned around me must have worked. On the night after the blackout, I dreamed! It was a basilisk rising up at the entryway of the warm motel room we had together. It is the same stone basilisk that was thick and twisting beneath Jesus’s bare foot in the church graveyard at my old prep school. All the boys held me and forced me to touch it when they found out it scared me. The basilisk and the memory of the boys are such old thoughts that I almost forgot them but I can’t think of anything else now. I thought of it all day while I ran copies of customer rental agreements. At lunch I did not gas up the company Hummer the way I meant to but I sat in the break room and drew the monster from memory. I use to be a pretty good artist. Is it normal to dream like this after a cleansing? On paper, this thing looks really stupid: like a snake with feathers and a beak, but in my dream its eyes were like silver points following me. Looking down just now, I realized I don’t have my ring on. Nat will kill me. Do you have it? Is this your way of giving me an ultimatum? Because I told you I’m not ready.

Love

Gerald

SENT FROM MY BLACKBERRY.

Inktober Fourth. “Spell.”

Before Natalie opens her eyes, she is awake and thinking: I will leave and I will not tell anyone where I’m going until I am back over the border. It is a serious thing to consider, but it excites her too. Natalie brews the last of her chai tea-bags and brings in those boys: Onion, and Fish. Only Fish comes back in to lap the wet food in his bowl. Natalie checks her watch. Gerald is never back before five-thirty. There is still time. Her skin feels tight with elation.

Even the gray and green Dollar Tree in town looks better to her after the fine thought she has had this morning. Natalie even finds the beets she wants on discount, cold to touch. Perfect. She keeps her budget in mind and buys menthols, a scratcher, and a bottle of beer. She gets back in the small blue Volvo and could have kept driving the roads but for Onion. Beyond the burnt down mill, where the land gets flat, she watches the paint horses running in their corral for a long time. She checks her small watch.

At home, Onion is missing, even after she calls out the back door for him. Fish watches her with golden saucers. She sets the quarts of water to simmering, thinking about her grandmother’s recipe, which has always made her feel better. But when she finishes the beets in her soup, Onion is still missing and Gerald isn’t home. Five-forty.

In Gerald’s slack pocket there is a crumpled piece of paper that seems blank except for a faint waxy slither when she tilts it in the golden light while the sun sets.

Inktober Third. “Roasted.”

Headlights on the curving mountain pass click on all at once. The shadows between the pines grow colder and bluer about Gerald. His bad eyes scan the surroundings from behind aviator eye-glasses. ‘Hunter’s eyes’ the boys use to say, even though Lizzie Beth was always better at drawing a bead. His hands are soft now. His middle fat. In the clearing out between two thin alders turning red from yellow-gold, Gerald sets his gas can down beside someone’s archaic radio: a politician’s tired voice strains the tones of rhetoric. Here, a white porcelain dutch oven. Vinyl strands fall away from the aluminum skeleton of a lawnchair occupied by skeleton leaves. A dirty bedroll turns the color of grime at the edges. And various-many shoes, in every shade of pastel; like scattered crayon pieces in the grass patches. Gerald is so hungry that he cannot help but check inside of the dutch oven for something to eat. -FM

Inktober Second. Tranquil.

Look down into the mountain town, Whistle Wood, whose every street is empty tonight in the season of the missing boy. See the stucco motel parking and its glass puddles reflecting the downcast gaze of a watcher. See the old mill’s plastic smokestacks billow cotton clouds. See the main street lined in lamps like Christmas. And see Hannah: who wanders after curfew, out in the mountain pass. Here is the unfinished corner store where she saw the missing boy. See Hannah’s small boots, and her hair shine and a careful smile rendered a little at a time. And the painter brushing her yellow rain slicker delicately — the color of tulips in the sun. -FM

Inktober First. Poisonous.

The lights wink out and the small thermostat in the wall too. She is so stifled that he opens the windows. He hangs his jacket. He will need it tomorrow. And he is watching her talk: about saving up for them in the summer. Disallowed from touching her — but he is holding her in the spot of his flashlight. And she is red elbows on pale skin.

He turns the flashlight on its handle with the light up at the ceiling in the room of warm shadows. His tie a gift from his children that she touches with disregard. Her hair descends around their faces like a curtain. Suddenly both of them are laughing again because of the extravagant cost they will pay for their lavish hearts.

When the lights come back on, they are gone. A burgundy carpet. Teal flowers in the golden wallpaper. An ice bucket. An unmade bed. A silver wedding band, in the jacket, hung up on the bathroom door. A small thermostat humming in the wall. -FM